(This is not AI-generated. It’s the required essay I submitted to Harvard University’s X AESTHINT15 Course “Rhetoric: The Art of Persuasive Writing and Public Speaking” – 8/8 peer- reviewed and graded)

“I’m not a racist; my sister-in-law is from Asia.”

“I’m not a racist; my best friend is from Africa.”

“I’m not a racist, but I can’t stand people from that country because …”

These kinds of statements reveal a troubling reality. Racism, as we once understood it, may no longer exist because biology and skin colour are blurred categories in today’s diverse societies. However, I urge you to look closer. Racism has not vanished; it has shifted form.

That new form is ethnicism.

Ethnicism is discrimination based not on your skin colour, but on your ethnic identity — your language, your nationality, your traditions, or even your accent. Unlike racism, ethnicism can exist between people who appear physically identical.

Ethnicism happens in workplaces when managers promote only those from their own ethnic group, even when others are just as qualified. Ethnicism happens in friendship circles when people whisper, “They don’t understand our humour.” Ethnicism happens in societies when certain groups are stereotyped, excluded, or constantly asked to “prove” where they belong. That single word “they” builds invisible walls that separate people who should be working together.

You might say: “Isn’t this just a matter of personal bias? Aren’t you overthinking everyday preferences or harmless jokes?”

The answer is no. Ethnicism is not harmless.

When we tolerate ethnicism, we limit our future. How many great discoveries, how much art, how much leadership and creativity have we lost because someone’s ethnic background caused doors to close before they had a chance to knock?

Consider the student with a strong accent who is mocked rather than mentored. The job candidate with a “foreign”-sounding surname whose resume is quietly pushed aside. The employee who works hard but never gets promoted because “they don’t quite fit in.” These are not just individual tragedies; they are collective losses. Every time we allow ethnicism to flourish, we silence ideas that could transform industries, communities, even nations.

Addressing ethnicism isn’t just a moral duty; it is a practical necessity. How do we confront this hidden form of discrimination?

Here are three ways.

Words matter

Language shapes perception. Phrases like, “But where do you really come from?” may sound innocent, but they carry heavy implications. They imply exclusion, “You are not truly one of us.” Words can wound or heal. We must choose words that bring people in, not push them out.

Actions matter

Even small actions can move mountains. Do not laugh along when someone mocks an accent. Do not excuse hiring decisions that are clearly biased. Do not overlook exclusion in social circles. Standing by silently is complicity. Speaking up, whether in a boardroom, classroom, or café, signals that ethnicism isn’t tolerated.

Awareness and humility matter

We are proud of our heritage, and rightly so, but pride must never become prejudice. We must examine our own biases honestly, admit when we are wrong, and commit to fairness in daily life. We must see people first as individuals, not as representatives of a stereotype.

Ethnicism may not always make the headlines like racism once did, but it is no less destructive.

Imagine a future where every child, regardless of their accent, surname, or cultural traditions, feels they belong. Imagine workplaces where promotions are earned through talent and merit, not determined by ethnicity or group affiliation. Imagine communities that celebrate our differences, not as divisions, but as sources of strength and unity.

So let us not turn a blind eye to ethnicism. Let us dismantle it wherever it appears. This fight is not only a moral obligation; it is a matter of survival, innovation, and justice.

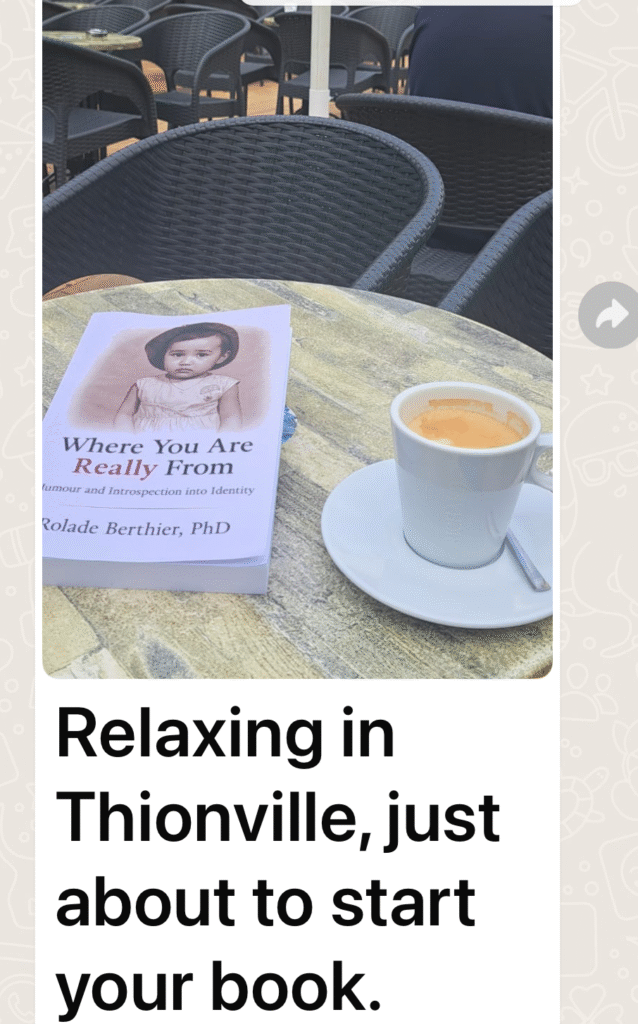

(I discuss the concept and reality of ethnicity in my book “Where You Are Really From”.)